Chaos in the Caucasus

A story that I stumbled upon

This is my first real piece of writing since I opened by Substack account. It’s an article that I recently had published in the Great War Group’s journal, “Salient Points.” The subject is far from my usual stuff of the Western Front and trench warfare, and I hope that my subscribers will find it as fascinating as I do.

Many readers of this journal will know that for many years I have been researching soldiers of the British Army for a living. The subjects are in most cases the forebears or relatives of the person who contacts me with a request for help. In a sense, the men are a random selection from the 8 million or so who passed through the ranks. Yet I am often surprised to find connections between the soldiers I have researched. Sometimes it is something fairly clear-cut and explicable like men from the same town who just happened to enlist into the same unit at the same time, or perhaps men who died close together in the same action. In the case that is described in this article, it concerns an officer and an “other rank” that I was asked to research more than a decade apart. They were from completely different backgrounds, yet I found that their two stories intertwined in a most intriguing way and the action is set in a place that is not usually considered to concern the British Army at all: the mountainous area between the Black and Caspian Seas generally known as the Caucasus.

In 1914, the Caucasus region fell across parts of the Ottoman Empire, Persia and the Tsarist Russian Empire, but it is today covered in part by Georgia, Armenia, eastern Turkey, northern Syria, Iraq and Iran, Azerbaijan, and the southern element of the Russian Federation. The area was and remains highly and often explosively diverse in terms of culture, language and religion. From late 1917 onwards, it saw widespread breakdown, anarchy, and violence. Five factors added to long-running problems with Kurds, Armenians, and others in the area: the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in October 1917; the organisation of counter-revolutionary “White” forces and what then amounted to civil war in Russia; the military defeat and breakup of the former Ottoman Empire; the rise of independent Georgia and Azerbaijan; and the growth of insurgent Muslim groups in Iraq.

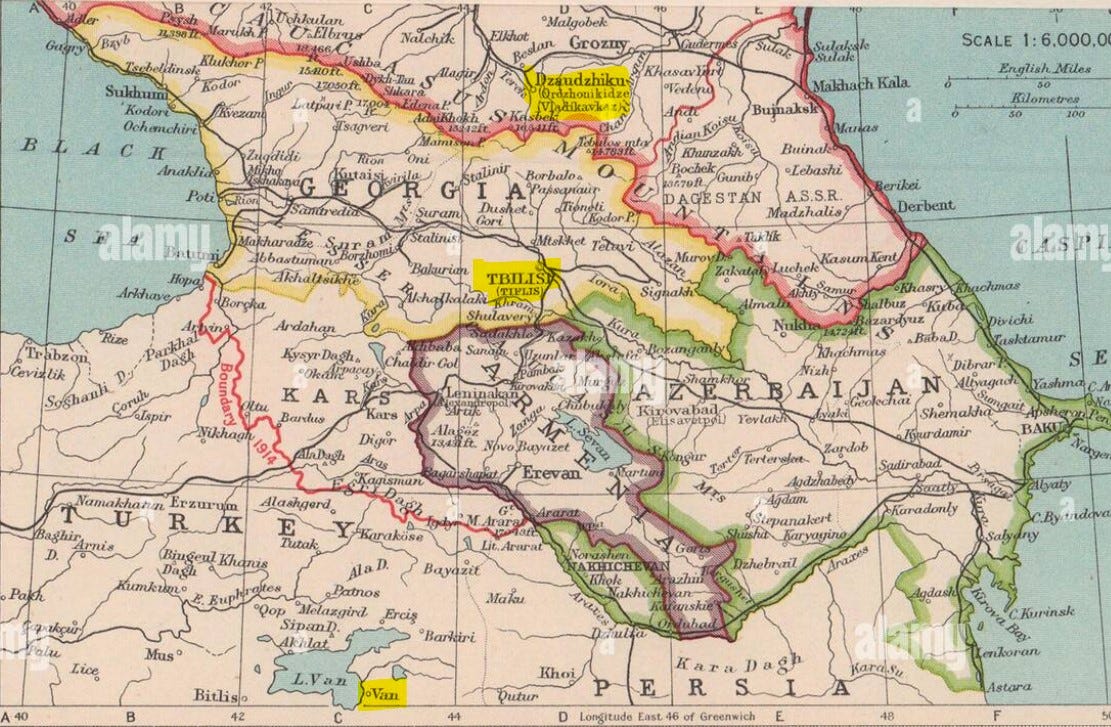

A map I found by Googling, with my highlights picking out some of the places I mention in the article: bottom to top, Van; Tiflis (or Tbilisi); and Vladikavkaz.

Let us begin with the dramatis personae.

James Douglas. I examined his story over ten years ago. He was born at Saline in Fife in Scotland in September 1878, the son of coachman Robert Douglas and his wife Catherine, née Bell. James married Agnes Darling at Oxnam in Roxburghshire in February 1906, and the registration shows that he had followed his father into the occupation of coachman. By 1911 they lived at Crailing. James served as Private M2/194380 of the Mechanical Transport of the Army Service Corps, and I found that he had been mobilised in July 1916, beginning his service at the Grove Park depot in London. As I will explain below, I found that was involved as a car driver in extraordinary escapades in the Caucasus. His two brothers were both killed in France: Thomas while serving with the Royal Garrison Artillery in September 1917, and Robert with the Seaforth Highlanders in March 1918.

The next character is not one that I was asked to research, but he proved to be key to understanding James Douglas’s story: George Marie Goldsmith. He had been born as George Marie de Goldschmidt: he legally changed it to Goldsmith in August 1914. Campaign medal documents say that he was with Intelligence Corps, but this hides a more shadowy role: he was in fact working for Mansfield Smith-Cumming, head of the Foreign Section (Secret Service Bureau) and just before war broke out he was sent for undercover work in Brussels. Goldsmith had originally enlisted into the ranks of the Imperial Yeomanry and saw service as such during the Second Boer War, but in August 1900 was commissioned into the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen’s Bays). Born in 1874, he had married and by June 1911 had two children. He had also become a stockbroker and a member of the London Stock Exchange. At the time of our story, he was a Captain and Douglas was his driver. His detailed report of events is held by the National Archives.

George Frederick Handel Gracey. I was asked to study him quite recently, and it was only as I began to dig in that I discovered that he too had been in the Caucasus. It made me look back at James Douglas’s story and to my surprise (my memory being terrible) I found I had mentioned him in my report. George was born at home in Belfast, coincidentally in September 1878. His parents were John Gracey, who was recorded on the birth registration was being an iron turner, and his wife Annie, née Woods. His parents had married in 1862, and George was the ninth of a family that would eventually consist of ten children. In the census of 1901 (the 1891 version no longer exists for Ireland), Annie is shown as a widow at Israel Street in Belfast, with four of her children including George, and two boarders. George was given as being 21 years of age, Presbyterian by faith, and had the occupation of joiner.

Before examining his military work, it is essential to understand why he was selected to do it. In 1904, George went overseas for missionary work. His destination was Urfa in Turkey, which is today called Şanlıurfa. It is situated near the southern Turkish border with Syria. The area had seen much recent trouble, particularly in 1895 when there were Muslim pogroms against local Armenian Christians, and for some time it had been the site of three foreign aid missions. Of these, the most likely to be the sponsor of George’s time at Urfa was the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. George developed a lifelong connection with the Armenians during his time at Urfa.

In July 1908, the “Young Turk” revolution took place in Turkey, and it appears to have been at this time that George relocated to Aleppo in Syria. He married Amelia Turnley Coulter there in October 1909. She gave birth to two children while they were situated at the city: Anna, born in 1910, and George junior, born a year later.

After some ten years overseas, George applied for a return home for a period of furlough. His British passport was issued on 7 May 1914, and usefully gives the route of the family’s journey through Damascus, Jerusalem, Haifa and Port Said. The exact date of arrival at home is not known but is not likely to have been before June 1914. It was stated in a much later newspaper report that for some time after the war was declared on 4 August 1914, George worked with the Young Men’s Christian Association in Ireland. There was much work for such an organisation, in, for example, providing accommodation and refreshment for many young men on the way to enlist or to their first training depot.

George’s third child, Stephen, was born in Belfast in January 1915 and the register still gives George’s occupation as missionary. His movements and work overseas before 1917 remain rather uncertain due to lack of evidence. His final child, Amelia, was born in Belfast in September 1916 and George is given as the informant for registration purposes: that is, he was in Belfast at the time. It is however clear from other information that he had certainly already been in Turkey again, so he had evidently returned home and went back out at some later date.

A newspaper report says that “in the spring [of 1916] the Russians … entrusted him with the resettling of the vilayet of Van.” There could scarcely be a more challenging assignment, especially for a civilian. The Tsarist Russian Empire had recently advanced into eastern Turkey, capturing a broad belt of Caucasus land that included Trebizon, Erzerum and the ancient city of Van, but only after to and fro fighting during which Van had seen an armed revolt against Turkish oppression. The city was a main centre of a culturally Armenian population, having been so since as early as the 2nd Century. The revolt and the arrival of friendlier Russian forces had the effect of bringing about a quarter of a million Armenian refugees into the city, which normally had a population of about 50,000. But it was not long before a Turkish counterattack temporary drove the Russians back. Petrified by what they knew was happening to Armenians elsewhere, some 150,000 fled from Van, going in the direction of Erevan as it became clear that Russian forces were retreating, and that Van would be again left to the mercies of the Turks. As many as 40,000 of these poor people died en route from a combination of violence and starvation. They were but a small proportion of Armenian loss during the Great War.

Then, “early in August [1916] … the [Russian] military authorities told him that the Armenians under his care should be withdrawn,” as enemy forces were nearing Van again. The urgency to get more Armenians out of Van must be set in the context that they had been subjected to genocide since the “Young Turk” revolution. At the orders of Talaat Pasha of Turkey, an estimated 800,000 to 1.2 million Armenians were rounded up and sent on death marches to Syria in 1915 and 1916. The deportees were deprived en route of food and water and subjected to violence, rape, robbery, and massacre. Once into the Syrian Desert, the survivors were herded into concentration camps. In 1916, another wave of pogrom was ordered, leaving only around 200,000 deportees alive by the end of the year. It is believed that somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 Armenian women and children were forcibly converted to Islam and integrated into Muslim households. Urgent evacuation from Van might save the lives of many, and it was entrusted to George Gracey.

The evacuation on foot of some 25,000 Armenians (and 7,000 cattle), covering 150 miles over six days to reach Igdiah (Igdir) in Russian territory, which included some initial organisation of armed militia to defend the route out of the vilayet, took place in the August and appears to have been organised almost single-handedly by George. This remarkable humanitarian feat appears to have gone unrecognised by the British authorities in terms of any national recognition or reward.

An American newspaper of December 1916 carried an article describing the evacuation, adding that George was now back in England trying to raise funds for further aid. It is evident from advertisements that he was doing the rounds, giving talks entitled “With the Armenian refugees in the Caucasus”. Meanwhile, Van remained in Russian hands until the whole area fell into further chaos in the wake of the October 1917 revolution.

On 27 November 1917, a recommendation was made to give George an army commission at the rank of Captain. This was unusual, and after questions were raised it was stated that it was a matter of “military necessity.” The commission was approved, and George began to operate as an army officer, although it was not formalised until 9 January 1918, at which time his seniority was backdated to 27 November 1917. He was made a Captain of the General List rather than of any particular regiment. George was posted to the Caucasus Military Agency, the intelligence section of the British Military Mission at Tiflis (today it is Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia but at the time was deep into Russian ground,) and was given some specific objectives. We shall return to this.

Colonel Geoffrey Davis Pike of the 9th Gurkha Rifles commanded the Caucasus Military Agency, and Gracey reported to him in this capacity. Born in 1880 in Sussex, he was the youngest and most experienced of the three officers in this tale, having been commissioned in 1900. He had gone to France as a Captain of his battalion in 1914 and served in the trenches with it until he was appointed GSO3 (Brigade-Major) in September 1915. In the June of that year, he had received the Military Cross from King George V at Buckingham Palace, marking him out as a very early recipient of this new award. Later in the war, Pike served in Mesopotamia and was then attached to the Russian Embassy in London, as his fluency in the Russian language had come to notice.

Now we know the players, let us unfold their Caucasus story with particular focus on where they come together.

With no surviving service record, it is difficult to know exactly when Private James Douglas went overseas, but in January 1918 he was one of three ASC Ford car drivers assigned to Captain George Goldsmith. He was at Baghdad and had just met with Major-General Lionel Dunsterville. The latter had been ordered to assemble a small body known as “Dunsterforce” which was to proceed to the Caucasus and work with local militias to in effect replace the recently collapsed Russian Caucasus Army, developing a protective cordon to stop Turkish (and now German) advances on the oil centre at Baku. Douglas drove with a detachment that left Baghdad on 22 January and proceeded via Khaniqin and Kermanshah to Hamadan. Preparations were to be made for a temporary headquarters for “Dunsterforce”. Delays and the poor state of the roads meant that the convoy did not arrive at Kermanshah until 29 January. Ahead, a Kurdish attack on a wireless station caused further delay, as the convoy waited until an armoured car had gone forward to clear the way. Hamadan was reached two days later.

On 4 February 1918, Dunsterville also arrived at Hamadan. Goldsmith was now ordered to take Douglas and the rest of his convoy on through Kurdistan and Azerbaijan to Enzeli, then possibly on to Baku, and make arrangements for the arrival of “Dunsterforce”. He began to move on 9 February. After hair-raising encounters with Cossacks and bandits assisting escaped German and Turkish POWs, the convoy reached Enzeli on 11 February. Goldsmith then negotiated for his small force to go on by sea to Baku on a steamer carrying Bolshevik soldiers home to Russia. When he arrived at Baku, he set about making arrangements for “Dunsterforce” to travel the same route, by buying a fleet to take them.

By 23 February, Goldsmith and his men had arrived by train at Tiflis (now Tbilisi, capital of Georgia). He there reported to Pike. The latter was not at all pleased with the prospect of the impending arrival of “Dunsterforce” in the area and gave Goldsmith fresh orders. He was to proceed to Erzerum to co-operate with the “White Russians” (monarchist, reactionary anti-Bolshevik forces).

Goldsmith’s band therefore went on to Erzerum and Sarakamish, where amongst other tasks they helped evacuate 4,000 Armenian women and children and also destroyed with bombs three stores containing 10,000 rubber tyres. They then returned to Tiflis. The entire region was by now essentially in a state of anarchy. Large bands of well-armed Tartars were raiding railway stations and trains, sacking villages, and “murdering Armenians wherever found”. James Douglas and the other poor ASC drivers must have been wondering what terrible trick of fate had brought them into this deadly area.

When George Gracey was given his initial instructions on his role as a member of the Caucasus Military Agency, he was to “go out and do his best to organise intelligence and sabotage” against the Ottoman Empire. Specifically, he was to gather information regarding the location of a railhead on the Baghdad railway; determine the rate of construction of the railway; determine whether Decauville (portable lengths of light railway track) were laid before construction of standard gauge; determine the amount of raft traffic on the River Tigris north of Mosul and identify enemy troop concentrations in areas between Diyarbekır and Jisne-ibn-Omar and around Mosul. His precise activity under these instructions is difficult to determine: spies tend not to leave notes. But we do know something, and it is where his story collides with that of James Douglas.

Goldsmith’s report mentions Douglas in connection with an attempt by Gracey to reach Maku in northern Persia. This was ultimately unsuccessful owing to severe fighting in the area, but was clearly bravely undertaken. Gracey had been ordered to Maku to try to persuade a local Sirdar to come over to the allied side and gain his help in reopening the Indo-European Telegraph Company’s telegraph line which was being wrecked by Tartar bands. The date is not given but appears to be around March 1918. James Douglas’s part in this is not explained but it would be reasonable to assume that he had been Gracey’s driver.

In May 1918, as Georgia was proclaiming independence and Tiflis was to be its capital, the British Military Mission withdrew northwards to Vladikavkaz, taking a large number of Armenian, Syrian, and Russian refugees with them. This meant crossing the Caucasus Mountains and entering what had previously been territory of the Russian Empire. In July 1918, Azerbaijan also became independent, with Baku its capital.

Formerly known as Ordzhonikidze and Dzaudzhikau, Vladikavkaz is now the capital city of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Russia. It is located in the southeast of the republic at the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, situated on the Terek River. The decision to move the Caucasus Military Agency from Tiflis into Vladikavkaz proved to be a poor one, for within a matter of weeks it came under attack by Bolshevik forces of what was becoming known as the Red Army. But before that happened, James Douglas was sent off on a quite extraordinary “Boy’s Own” mission.

In the early hours of 25 May 1918, James drove a Ford car carrying Goldsmith and a guide of the Ingush Muslim tribe from Vladikavkaz, going towards Kazbek in the area south of Erevan. They were attempting to reach a group of British, French, Italian and other consuls and in some cases their wives, with a view to extracting them from what was an increasingly hostile area. A few hundred yards after crossing Dariel Bridge the car came under fire, which killed the guide. It is not clear from the report whether this was fire from the Bolshevik force at and near the bridge or from another source. The intrepid Douglas carried on, and rescue was effected. Goldsmith recommended Douglas for his great gallantry, which eventually lead to the award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The citation appeared in the “London Gazette” in 1920 (the late date of publication being due to what happened next). The citation says that the consuls were located at Kazbek Mountain: it its my speculation that they had hidden in Gergeti Trinity Church as it is just about the only suitable place in the region.

Gergeti Trinity Church today.

On 6 August 1918, Vladikavkaz itself finally came under attack by Bolshevik forces. Colonel Pike was killed there on 15 August, and it appears that George Gracey was present throughout what amounted to a siege that only ended with the Bolshevik capture of the town. Gracey’s service record hints that he was twice wounded during this period of operations. It is my assumption that he took command of the Mission on Pike’s death. The latter had apparently been advised to take shelter, but he looked out of a window to observe what was going on, and was struck by a bullet.

Goldsmith, Gracey and Douglas were all taken into captivity by the Bolsheviks on 6 October 1918. They were moved at first to Astrakhan, then to Moscow. All manner of things were taken from the men during searches, in which Douglas lost his rubber boots – no doubt a precious commodity at that time of year.

On 19 May 1919, George Gracey was repatriated to allied hands at the Finnish frontier, in exchange from Admiral Fydor Raskolnikov, the commander of the Caspian Flotilla who would go on in 1920 to command the Bolshevik Baltic Fleet. Goldsmith and Douglas also formed part of this prisoner exchange.

There is, I am sure, much more of this rather exciting and intriguing story, buried in the archives.

Links